Overview

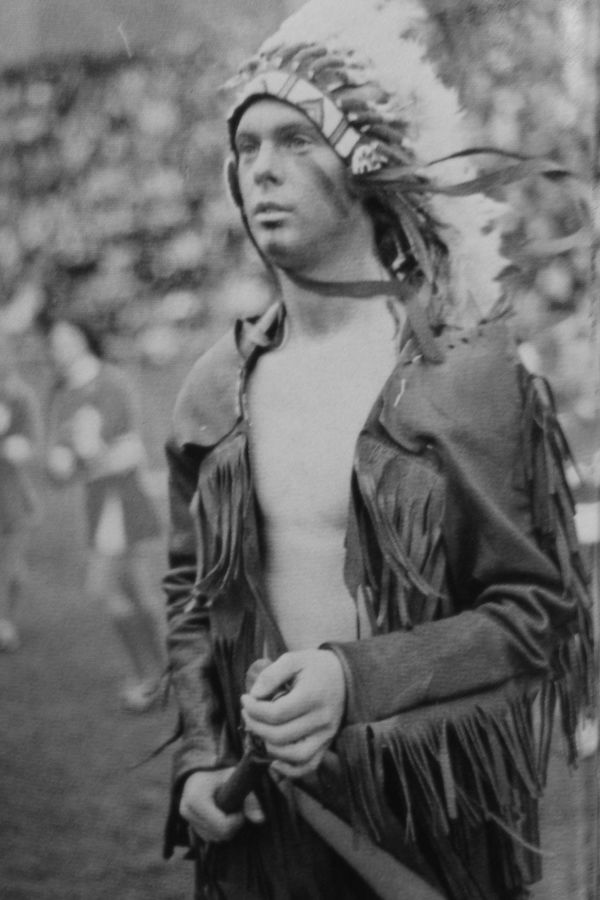

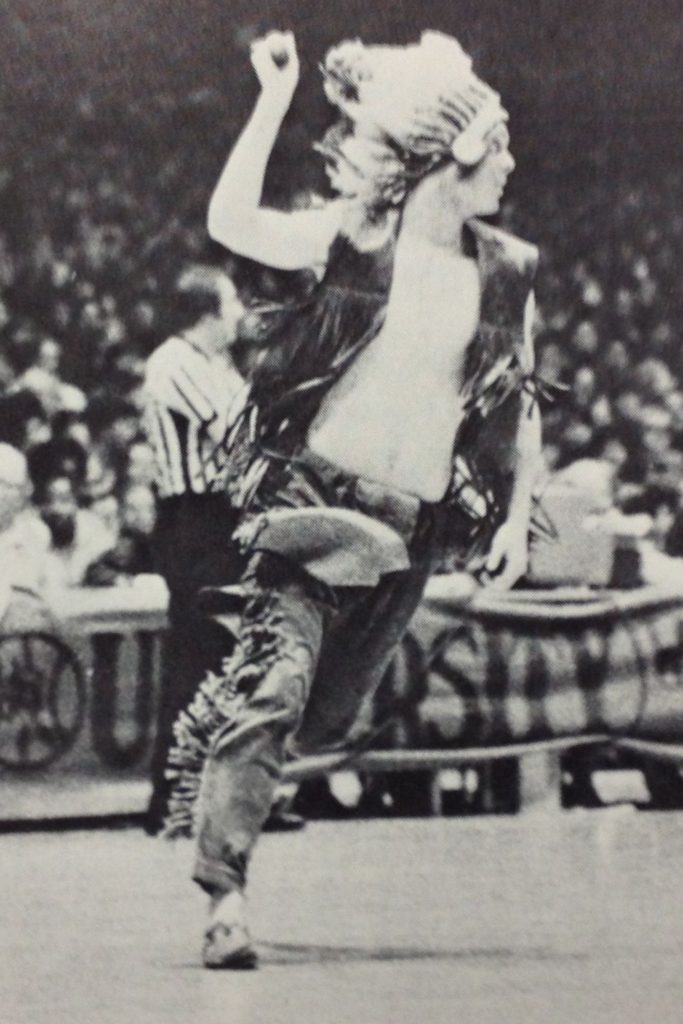

Saltine Warrior mascot at an SU football game in 1977.

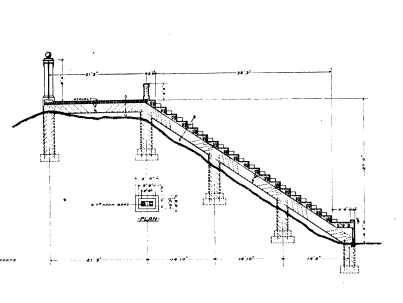

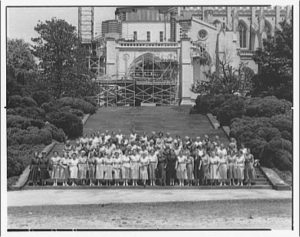

The Saltine Warrior was the official mascot of Syracuse University for 47 years from 1931 to 1978. The article claims excavation revealed the ancient location of an Onondagan “fortress or tribal house” which had been destroyed by a fire but included the remains of arrowheads, flint instruments, and fragments of textile. The Orange Peel credits Dr. Burges Johnson for the announcement of the archaeological findings. The Orange Peel writes “for nearly two years campus experts have been working quietly upon those textile fragments” in order to reveal “the portrait of an early Onondagan chief” painted by Hibbardus Kleine, “undoubtedly one of those intrepid Jesuit explorers” first to visit the area. The name of the Chief depited in the portrait was “O-gee-ke-da Ho-schen-e-ga-da”, which The Orange Peel claimed translates to mean “The Salt (or salty) warrior” in English . The statue currently stands in the south-east corner of Shaw Quadrangle next to the Shaffer Art Building.

For 45 years, many people believed the legend of the Saltine Warrior was true. This was due in large part to media reports as factual by The Daily Orange, The Alumni News, and downtown Syracuse papers . “The thing that offended me when I was there was that guy running around like a nut. That’s derogatory” Lyons explained . Onkwehonweneha arranged a meeting with the Onondaga Nation Council of Chiefs and brothers of Lambda Chi in an effort to relieve tension over the mascot removal 28. George-Kanentiio recalls the meeting:

For 45 years, many people believed the legend of the Saltine Warrior was true. This was due in large part to media reports as factual by The Daily Orange, The Alumni News, and downtown Syracuse papers . “The thing that offended me when I was there was that guy running around like a nut. That’s derogatory” Lyons explained . Onkwehonweneha arranged a meeting with the Onondaga Nation Council of Chiefs and brothers of Lambda Chi in an effort to relieve tension over the mascot removal 28. George-Kanentiio recalls the meeting:

“During a remarkable session in the old communal longhouse at Onondaga, the brothers of Lambda Chi, the Native students of SU and the Onondaga chiefs met to discuss this issue. Some type of magic was certainly in the air because when we left that session some hours later, the Lambda Chi organization agreed with us that the Warrior must be put to rest. These young men went on to become our most vigorous supporters in whatever we did at SU.” 29

Onkwehonweneha used the Saltine Warrior controversy as a way to spread campus awareness on Native American issues 30. The support that Onkwehonweneha received from Chancellor Melvin A. Eggers opened the doors to increasing Native awareness by sponsoring Native speakers, holding various social events, and introducing classes on Iroquois culture 31.

Conclusion

During this time, the issue of Native Americans as mascots became a national movement. Schools all over the country were abolishing their Native American mascots, Syracuse University being one of the first. Today, Syracuse University of has a Native American Studies program within the College of Arts and Sciences. The program offers a and a 32. Syracuse University also offers the to qualified students who receive financial assistance equal to the cost of tuition, housing and meals. The Haudenosaunee Promise Scholarship Program ”seeks to make the rich educational experiences of Syracuse University available to admitted, qualified, first-year and transfer American Indian students.” 33

- “Syracuse University History: Syracuse University Mascots.” Syracuse University Archives. Syracuse University, n.d. Web. 18 February 2013. ↩

- “Syracuse University History: Syracuse University Mascots.” Syracuse University Archives. Syracuse University, n.d. Web. 18 February 2013. ↩

- Reigelhaupt, Barbara. “Students Research Warrior Saga’s Origin.” The Daily Orange, 23 March 1976. Microfilm. 18 February 2013. ↩

- “Syracuse University History: Syracuse University Mascots.” Syracuse University Archives. Syracuse University, n.d. Web. 18 February 2013. ↩

- “The True Story of Bill Orange.” The Syracuse Orange Peel, October 1931. Syracuse University Archives. 18 February 2013. ↩

- “The True Story of Bill Orange.” The Syracuse Orange Peel, October 1931. Syracuse University Archives. 18 February 2013. ↩

- “Syracuse University History: Syracuse University Mascots.” Syracuse University Archives. Syracuse University, n.d. Web. 18 February 2013. ↩

- Reigelhaupt, Barbara. “Myth of Saltine Warrior Foolum SU Many Moons.” The Daily Orange, 23 March 1976. Microfilm. 18 February 2013. ↩

- Reigelhaupt, Barbara. “Students Research Warrior Saga’s Origin.” The Daily Orange, 23 March 1976. Microfilm. 18 February 2013. ↩

- Reigelhaupt, Barbara. “Students Research Warrior Saga’s Origin.” The Daily Orange, 23 March 1976. Microfilm. 18 February 2013. ↩

- Reigelhaupt, Barbara. “Myth of Saltine Warrior Foolum SU Many Moons.” The Daily Orange, 23 March 1976. Microfilm. 18 February 2013. ↩

- Reigelhaupt, Barbara. “Myth of Saltine Warrior Foolum SU Many Moons.” The Daily Orange, 23 March 1976. Microfilm. 18 February 2013. ↩

- “Syracuse University History: Syracuse University Mascots.” Syracuse University Archives. Syracuse University, n.d. Web. 18 February 2013. ↩

- Reigelhaupt, Barbara. “Myth of Saltine Warrior Foolum SU Many Moons.” The Daily Orange, 23 March 1976. Microfilm. 18 February 2013. ↩

- Reigelhaupt, Barbara. “Myth of Saltine Warrior Foolum SU Many Moons.” The Daily Orange, 23 March 1976. Microfilm. 18 February 2013. ↩

- Reigelhaupt, Barbara. “Myth of Saltine Warrior Foolum SU Many Moons.” The Daily Orange, 23 March 1976. Microfilm. 18 February 2013. ↩

- Reigelhaupt, Barbara. “Myth of Saltine Warrior Foolum SU Many Moons.” The Daily Orange, 23 March 1976. Microfilm. 18 February 2013. ↩

- “Onondaga Indian Fact Sheet.” Native American Facts for Kids.Native Languages of the Americas, n.d. Web 29 March 2013 ↩

- George-Kanentiio, Doug. Personal Interview. 9 April 2013. ↩

- George-Kanentiio, Doug. Personal Interview. 9 April 2013. ↩

- George-Kanentiio, Doug. Personal Interview. 9 April 2013. ↩

- George-Kanentiio, Doug. Personal Interview. 9 April 2013. ↩

- McEnaney, Maura. “SU Drops Saltine Warrior”. The Daily Orange, 18 January 1978. Microfilm. 18 February 2013 ↩

- McEnaney, Maura. “SU Drops Saltine Warrior”. The Daily Orange, 18 January 1978. Microfilm. 18 February 2013 ↩

- Coffey, Thomas. “Save the Mascot.” The Daily Orange, 3 March 1978. Microfilm. 18 February 2013. ↩

- Onkwehonweneha. “Letter: Warrior Based on a Lie”. The Daily Orange, 3 March 1978. Microfilm. 18 February 2013. ↩

- George-Kanentiio, Doug. Personal Interview. 9 April 2013. ↩

- George-Kanentiio, Doug. “Natives Saw Chancellor’s Moral Center.” Syracuse University Archives, Chancellor Melvin C. Eggers Files. Syracuse Post-Standard, 8 January 1995 ↩

- George-Kanentiio, Doug. “Natives Saw Chancellor’s Moral Center.” Syracuse University Archives, Chancellor Melvin C. Eggers Files. Syracuse Post-Standard, 8 January 1995 ↩

- George-Kanentiio, Doug. “Natives Saw Chancellor’s Moral Center.” Syracuse University Archives, Chancellor Melvin C. Eggers Files. Syracuse Post-Standard, 8 January 1995. ↩

- George-Kanentiio, Doug. “Natives Saw Chancellor’s Moral Center.” Syracuse University Archives, Chancellor Melvin C. Eggers Files. Syracuse Post-Standard, 8 January 1995. ↩

- ↩

- ↩